Te Whanau a Kai chairman Dave Hawea

A nui te mihi ki a koutou ngā kaitiaki o taua whenua mo tou koutou ra whakahirahira e heke mai nei.

On behalf of Te Whanau a Kai, we wish you all the best for the future.

It is very pleasing to see the arboretum having been established and lovingly maintained on these lands for the benefit of all.

The following is a small account of our history. Engari he iti he pounamu — although small it is of greenstone and therefore precious.

Eastwoodhill Arboretum stands on part of the Okahuatiu block. These were the lands of Ngati Hine, one of several hapu that make up Te Whanau a Kai iwi.

Te Whanau a Kai are of the Patutahi and Waituhi areas and inland recesses bordering on Matawai and Lake Waikaremoana.

An old footpath was used by our ancestors to connect Patutahi pa in the east to Ngatapa pa and beyond.

This path runs through Eastwoodhill following the high ridge at the back of the arboretum. Its common name today is Arateitei.

The path begins from a seam of sandstone in the Tangimate stream, referred to as Taumatapoupou stream on the map.

This stream follows Wharekopae Road to the Hihiroroa corner before crossing into the Eastwoodhill flats.

The name Tangimate refers to the deaths in a fight between Te Whanau a Kai and Tūhoe ( Ngāi Tūhoe, Te Urewera in the eastern North Island.) It was the last fight in the 1820s, and many people were killed, including the ope taua (warrior group) chief Tawhaki and his daughter.

This gave rise to the name Puraihotangihia, the crying for the loss of the maternal line, and the loss of the umbilical cord.

Tawhaki’s daughter had no issue — this line of genealogy was wiped out and due to this loss, Tawhaki does not feature in any whakapapa today.

Unfortunately, we do not know the origin of greenstone taonga that were found at the Eastwoodhill gateway during the 1920s, but it could be that they were buried for safety by Tawhaki’s party and with their demise, were lost to the iwi.

Anyway, that old footpath crosses the Tangimate just over the road from what was the Jobson’s driveway on the Hihiroroa Road.

It then rises up the steep ridge that forms the backdrop to most of Eastwoodhill.

The views from the high points there stretch from Hikurangi Mountain in the north to Maungatapere Mountain out west, with glimpses into Tūhoe lands.

Using these high ridges, the people were able to protect themselves on their journeys, as they could scan the countryside. If there were other parties using the land, their cooking fires would be seen.

The hills and valleys around Eastwoodhill were used for bird catching — Weka in particular — and also for trapping Kiore, the native rat.

We know that our people stopped along the way for a breather and to cook kai, and we understand evidence of small cooking fires have been found along that ridge which is Eastwoodhill’s back boundary.

This path was also used by Te Kooti and his ope whakarau (a group who broke free from the Chathams Island prison) in 1869. They were heading for the pa on the Maketu stream just up from the Wharekopae Falls, before their destination, Ngatapa pa — for what they hoped was shelter and safety.

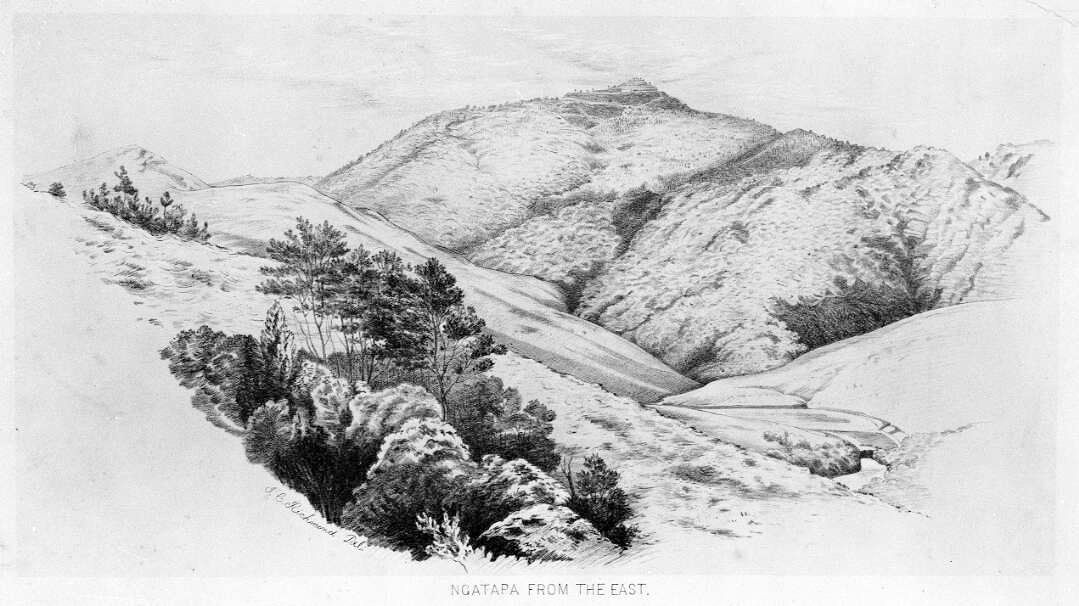

The kawanatanga (government) forces chasing Te Kooti used the same path. Ngatapa was a formidable pā, standing 700 metres (2,300 ft) above sea level and surrounded by cliffs on three sides and dense bush on the side facing any opposing force. Te Kooti had hastily begun strengthening its defences with earthworks.

Ngatapa pa, on the summit of the hill, scene of a four-day siege in January 1869.

This four-day siege resulted in the defeat of Te Kooti, who escaped with less than half his original force and many residents of Ngatapa pa were also killed during the battle.

Ngatapa, which memorialises the ancient fortified pa at this place, also now lends its name to the marae built on the hill Puketakawa adjacent to this school (takawa – the fruit of the kawakawa). The land was given to the Tuhoe people who were living at Pakowhai marae when Eria Raukura was stationed there, as a minister for the Ringatu Church, and members of Te Whanau a Kai gave their shares in the land behind the school as a place for a permanent home.

But Okahuatiu, the sacred maunga of Te Whanau a Kai, will continue to watch over the land and the people even if cloaked in a new garment, from the Tumanako family, who have 16 generations of connection to the very land they live upon, to the Cave family, whose connections to Williamson sees them also immediately tied to this land for some six generations (some 125 years of family connection).